Karachi is a big city. On most days, it is chaotic, loud, swirling and brash. But inside the gates of a century-old crematorium in Lyari town, there are few sounds.

Its only occupants today are crows, sparrows and pigeons. Occasionally, the birds would leave the shade of a nearby neem tree to feed on the dried rice left behind by Hindu families. Outside, a small signboard reads “Gujjar Hindu Community Burial and Cremation Ground.”

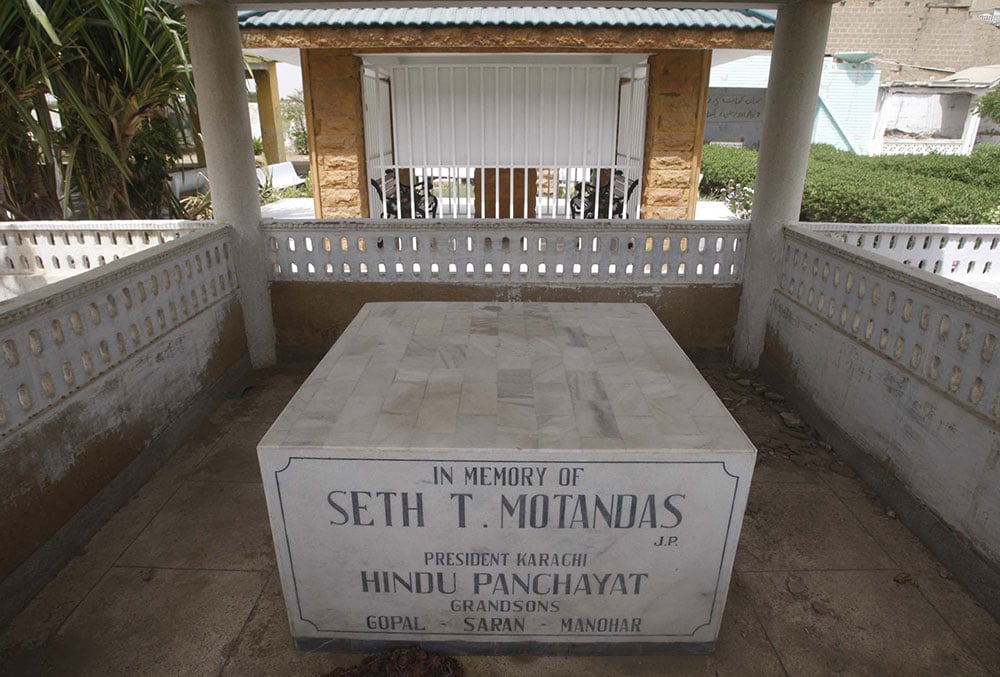

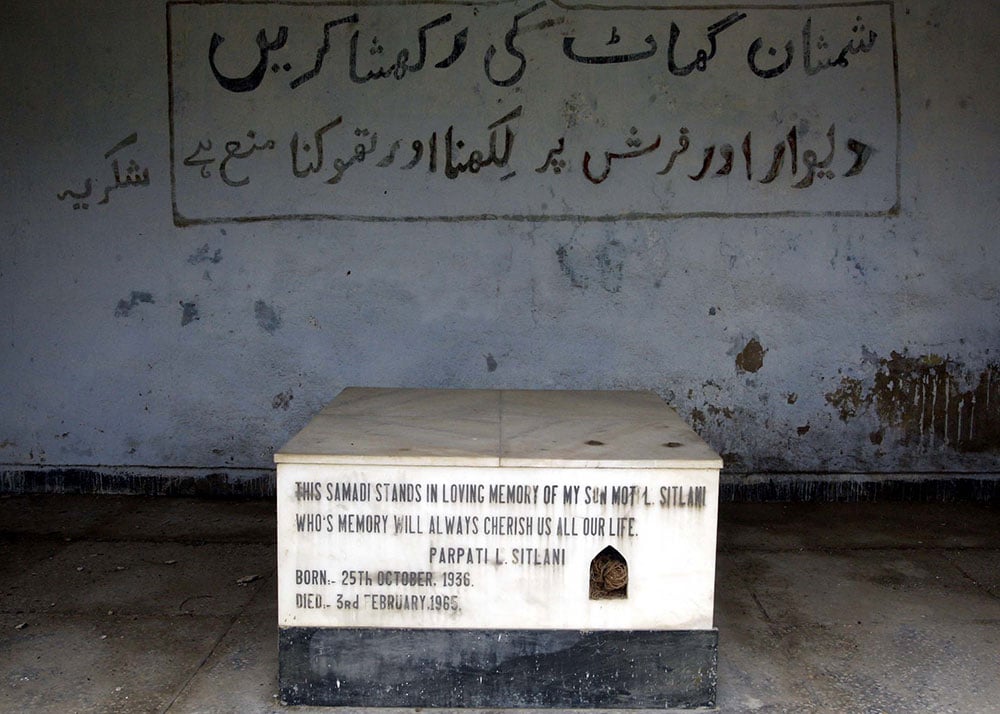

Constructed during the British rule in the subcontinent, the ground is spread over 22-acres. It is Karachi’s biggest cremation facility for its Hindu community. The names on the gravestones are etched in Sindhi, Urdu, English and Gujarati.

Yet, today, like most days, the city’s largest crematorium is quiet. It is rare for it to be buzzing with activity.

There is a misconception, amongst those who are avid consumers of Indian movies that Hindus only cremate dead bodies. In Pakistan, 80 percent of the approximately seven million Hindus bury their dead instead. This is because a large chunk of the Hindu population belongs to the so-called lower caste or Dalits. These families live in southern Sindh and are poor and marginalised.

A cremation ritual can cost between Rs.8, 000 to Rs.15, 000, since wood, dry coconuts, joss sticks and dry fruits need to be arranged.

“Majority of the lower caste Hindus belong to the Thar Desert,” explains Maharaj Nihalchand Giyanchandani, a pundit from the Sanghar District of Sindh, “This desert has a history of prolonged droughts.” In 1899, the notorious Chhapno drought struck the area, he adds. A large number of people were dying every day due to hunger and diseases. Since arranging to cremate each body was costly and difficult, the people of the area began to bury the dead in mass graves. That practice continues to this day.

But cremation is a central part of Hindus’ religious belief. In Hinduism, it is believed that the human body is made of five elements – earth, water, fire, air and sky. “When a person dies, each of these elements return to its origin,” pundit Maharaj Giyanchand Solanki tells Geo.TV, “The soul goes back to the sky. The body meets fire, its smoke meets [the] air and the ashes are immersed into water.”

Hence, in order to ensure that some requirements of the fiery dissolution are intact, Hindus of Sindh will burn a part of the corpse before putting it underground, such as a hand or a foot with joss sticks.

What also sets their burial process apart from the local Muslims is the way the graves are dug up. Some Hindus bury their dead in a sitting position. Family members and relatives would shape the body in a lotus posture – therefore sitting cross-legged in a meditative pose. For this, a round pit, rather than rectangular, is dug up and a cone-shaped tomb built on top.

A scepticism, gaining much traction recently, is that some Pakistani Hindus are forced to bury the dead due to lack of crematoriums and facilities for them to perform their religious rites in the country. But the local community rubbishes such claims. “The government of Pakistan has nothing to do with it,” says Ashok Kumar, a young Hindu leader from Lyari, “We choose to follow the burial practice. In fact, the Sindh government has recently allotted us more land for our graveyards.”

– Guriro is a Karachi-based journalist. He tweets @amarguriro