India remains unable to outgrow the colonial legacy. The legal and educational systems confirm that the decolonisation of the mind is among the greatest challenges today’s Indians have to face. – Shashi Tharoor

India remains unable to outgrow the colonial legacy. The legal and educational systems confirm that the decolonisation of the mind is among the greatest challenges today’s Indians have to face. – Shashi Tharoor

I recently wrote to the government of India to propose that one of India’s most renowned heritage buildings, the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata, be converted into a museum that displays the truth of the British Raj—a museum, in other words, to colonial atrocities.

This famous monument, built between 1906 and 1921, stands testimony to the glorification of the British Raj in India. It is time, I argued, that it be converted to serve as a reminder of what was done to India by the British, who conquered one of the richest countries in the world (27 percent of global gross domestic product in 1700) and reduced it to, after over two centuries of looting and exploitation, one of the poorest, most diseased and most illiterate countries on Earth by the time they left in 1947.

Why do we need a museum?

It is curious that there is, neither in India nor in Britain, any museum to the colonial experience. London is dotted with museums that reflect its imperial conquests, from the Imperial War Museum to the India collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum itself.

But none says anything about the colonial experience itself, the destruction of India’s textile industry and the depopulation of the great weaving centres of Bengal, the systematic collapse of shipbuilding, or the extinction of India’s fabled wootz steel.

Nor is there any memorial to the massacres of the Raj, from Delhi in 1857 to Amritsar in 1919, the deaths of 35 million Indians in totally unnecessary famines caused by British policy, or the “divide and rule” policy that culminated in the horrors of Partition in 1947 when the British made their shambolic and tragic Brexit from the subcontinent. The lack of such a museum is striking.

Surprisingly, large sections of both Indians and British still remain unaware of the extent of these imperial crimes against humanity.

This became evident when a speech I made at an Oxford Union debate in 2015, on whether Britain owed its former colonies reparations, went viral. Whereas I assumed that everyone knew the issues involved, the speech’s online popularity revealed that millions felt I had opened their eyes to their own history.

My Indian publisher, David Davidar, persuaded me to write a book on the British Empire in India that expanded on my Oxford arguments. The resulting volume, An Era of Darkness, published in the United Kingdom as Inglorious Empire, has become a bestseller in both countries.

Self-serving ‘benefits’

But while the facts and figures the book provides on colonial wrongs could all serve as lasting reminders of the iniquities of the Raj, some may still surprise.

Many apologists for British rule have argued that there were several benefits to India from it; the most common example cited is the Indian Railways, portrayed as a generous British endowment to knit the country together and transport its teeming millions.

But in reality, the railways were conceived, designed and intended only to enhance British control of the country and reap further economic benefits for the British.

Their construction was a big colonial scam, through which British shareholders made an absurdly high return on capital, paid for by the hapless Indian taxpayer.

Thanks to guaranteed returns, there was no check on spending, and each mile of Indian railway construction in the 1850s and 1860s cost an average of $22,000, as against $2,500 in the United States at the same time.

Indian passengers paid unfairly high rates, while British companies paid the lowest freight charges in the world. It was only after Independence that these priorities were reversed.

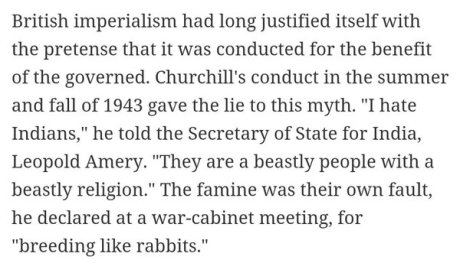

Similarly, some imperial nostalgics speak of Britain’s high-minded administration of the Empire, supposedly for the benefit of the natives. In practice, they ruled India for themselves, and were privately quite candid about their own motives.

The British basked in the Indian sun and yearned for their cold and fog-ridden homeland; they sent the money they had taken off the perspiring brow of the Indian worker to England; and whatever little they did for India, they ensured India paid for it in excess.

And at the end of it all, they went home to enjoy their retirements in damp little cottages with Indian names, their alien rest cushioned by generous pensions supplied by Indian taxpayers.

Leftovers of the colonial era

In the process, they left behind many less tangible legacies of British colonialism that continue to affect Indians.

These include the parliamentary system of democracy, enshrined by Indian nationalists in their Constitution for an independent India, which reflected the very British parliamentary democracy that Indians had been excluded from.

The Westminster model of democracy, devised in a tiny and homogeneous island nation, is unsuited to a vast and diverse country like India.

It requires the election of the legislature in order to form the executive, resulting in legislators less interested in law-making or government accountability than the prospect of executive authority.

India has been saddled with all the inefficiencies such a system creates in a diverse multi-party polity, whereas the presidential form of government practised in the US might have provided the stability required for effective decision-making unencumbered by unstable legislative majorities. But the British model prevailed, as it has in most of Britain’s former colonies.

Obsolete colonial laws continue to apply in India, which inherited a penal code drafted in the Victorian era.

The sedition law in India was worse than the equivalent law in Britain because it was written explicitly to oppress the colonised people.

Similarly, homosexuality is outlawed under Section 377 of the code in denial of the liberal standards of Indian society reflected in the ancient Hindu texts, which were suppressed when the British imposed Victorian attitudes to permissible sexual behaviour on India.

Ironically, the British have dropped both prohibitions themselves, but India remains unable to outgrow the colonial legacy. The legal and educational systems confirm that the decolonisation of the mind is among the greatest challenges today’s Indians have to face.

This is why the need for a place to house permanent exhibits about what the British did to India is compelling.

An enduring reminder is needed, both for Indian schoolchildren to educate themselves and for British tourists to visit for their own enlightenment. As I say to young Indians: if you don’t know where you have come from, how will you appreciate where you are going? – Aljazeera, 12 March 2017

» Shashi Tharoor is an elected member of India’s parliament and chairs its Foreign Affairs Committee. He is the prize-winning author of sixteen books, including, most recently, Inglorious Empire: What the British Did To India.

Source: https://bharatabharati.wordpress.com/2017/03/15/convert-the-victoria-memorial-in-kolkata-into-a-colonial-atrocity-museum-shashi-tharoor/