While yoga is not a “religion” in the sense that the Abrahamic religions are, it is a well-established spiritual path. Its physical postures are only the tip of an iceberg, beneath which is a distinct metaphysics with profound depth and breadth. Its spiritual benefits are undoubtedly available to anyone regardless of religion. However, the assumptions and consequences of yoga do run counter to much of Christianity as understood today. This is why, as a Hindu yoga practitioner and scholar, I agree with the Southern Baptist Seminary President, Albert Mohler, when he speaks of the incompatibility between Christianity and yoga, arguing that “the idea that the body is a vehicle for reaching consciousness with the divine” is fundamentally at odds with Christian teaching. This incompatibility runs much deeper.

Yoga’s metaphysics center around the quest to attain liberation from one’s conditioning caused by past karma. Karma includes the baggage from prior lives, underscoring the importance of reincarnation. While it is fashionable for many Westerners to say they believe in karma and reincarnation, they have seldom worked out the contradictions with core Biblical doctrines. For instance, according to karma theory, Adam and Eve’s deeds would produce effects only on their individual future lives, but not on all their progeny ad infinitum. Karma is not a sexually transmitted problem flowing from ancestors. This view obviates the doctrine of original sin and eternal damnation. An individual’s karmic debts accrue by personal action alone, in a separate and self-contained account. The view of an individual having multiple births also contradicts Christian ideas of eternal heaven and hell seen as a system of rewards and punishments in an afterlife. Yogic liberation is here and now, in the bodily state referred to and celebrated as jivanmukti, a concept unavailable in Christianity and in an afterlife somewhere else. Ironically, the very same Christians who espouse reincarnation also long to have family reunions in heaven.

Yogic liberation is therefore not contingent upon any unique historical event or intervention. Every individual’s ultimate essence is sat-chit-ananda, originally divine and not originally sinful. All humans come equipped to recover their own innate divinity without recourse to any historical person’s suffering on their behalf. Karma dynamics and the spiritual practices to deal with them, are strictly an individual enterprise, and there is no special “deal” given to any chosen group, either by birth or by accepting a system of dogma franchised by an institution. The Abrahamic religions posit an infinite gap between God and the cosmos, bridged only in the distant past through unique prophetic revelations, making the exclusive lineage of prophets indispensable. (I refer to this doctrine elsewhere in my work as history-centrism.) Yoga, by contrast, has a non-dual cosmology, in which God is everything and permeates everything, and is at the same time also transcendent.

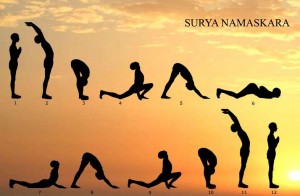

The yogic path of embodied-knowing seeks to dissolve the historical ego, both individual and collective, as false. It sees the Christian fixations on history and the associated guilt, as bondage and illusions to be erased through spiritual practice. Yoga is a do-it-yourself path that eliminates the need for intermediaries such as a priesthood or other institutional authority. Its emphasis on the body runs contrary to Christian beliefs that the body will lead humans astray. For example, the apostle Paul was troubled by the clash between body and spirit, and wrote: “For in my inner being I delight in God’s law; but I see another law at work in the members of my body, waging war against the law of my mind and making me a prisoner of the law of sin at work within my members. What a wretched man I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death?” (Romans 7:22-24).

Most of the 20 million American yoga practitioners encounter these issues and find them troubling. Some have responded by distorting yogic principles in order to domesticate it into a Christian framework, i.e. the oxymoron, ‘Christian Yoga.’ Others simply avoid the issues or deny the differences. Likewise, many Hindu gurus obscure differences, characterizing Jesus as a great yogi and/or as one of several incarnations of God. These views belie the principles stated in the Nicene Creed, to which members of mainstream Christian denominations must adhere. They don’t address the above underlying contradictions that might undermine their popularity with Judeo-Christian Americans. This is reductionist and unhelpful both to yoga and Christianity.

In my forthcoming book, The Audacity of Difference, I advocate that both sides adopt the dharmic stance called purva-paksha, the practice of gazing directly at an opponent’s viewpoint in an honest manner. This stance involves a mastery of the ego and respect for difference, and the hope is that it would usher in a whole new level of interfaith colaborations.